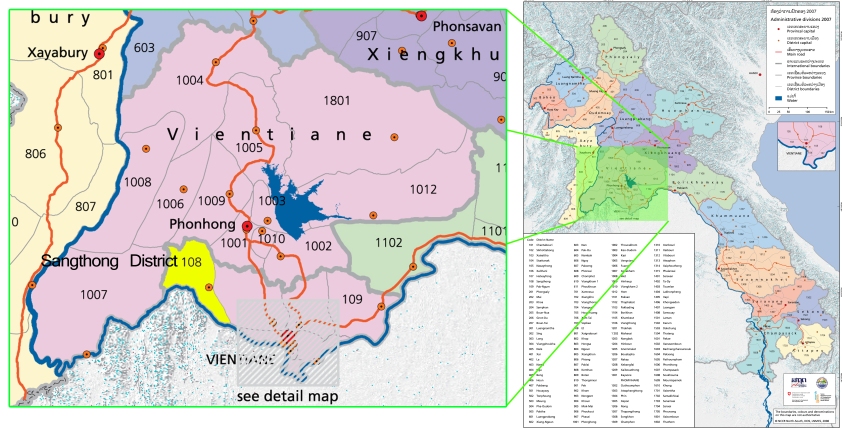

In 1992 MCC did an evaluation of its program in the Lao PDR which confirmed what MCC country representatives had long maintained: MCC should be looking at projects that integrated all areas of development in village communities with a focus on the long-term and the sustainable. In 1993 MCC proposed working jointly with local governments to implement such projects in Samphan and Vieng Xai, two districts in which the organization had a long history of working. The government approved the Vieng Xai site, but Mai district of Phong Saly was chosen over Samphan, as access to the villages in the latter was considered too difficult. Four villages in each district were selected and initial projects included family gardens, contour hedge farming, clean water systems and teacher upgrading. By the end, the project was implemented in 16 villages in Mai district and 13 villages in Vieng Xai.

The Integrated Rural Development Project (IRDP) started with the goals of improving the quality of life in the target villages, and developing the capacity of district government counterparts to give them the skills and experience to carry out a planned and systematic integrated development program. Quality of life issues were broken down into food security, basic health care and accessible basic education. Since the inception of the IRDP project, MCC staff also undertook projects to improve women’s development.

A variety of activities supported increased food security in villages from family gardens to small animal loans to addressing the problems in insufficient rice production. MCC applied the experience gleaned from alley cropping projects in Xaignabouli Province to encourage farmers in IRDP villages to use this alternative farming method. Experimenting with and extending higher yielding upland rice varieties decreased the period of rice shortage for many families in the project areas. Water availability, another difficulty with highland agriculture, were addressed through irrigation systems in many of the villages. While not directly improving food security, rice banks established in project villages allowed farmers to focus their attentions on rice production during the planting season.

Women in Vieng Xai, 1999

The IRDP started fruit tree nurseries in both districts which produce and distribute seedlings to farmers. In 1999 the Vieng Xai nursery produced 5,000 sweet plum, orange, pomello and longan seedlings. Training in grafting and fruit tree propagation was also made available to interested farmers.

Loans were extended to villagers at every IRDP location to purchase chickens and pigs, and trained village veterinary workers educated loan recipients on caring for their animals. Animal vaccines were made available to villagers at reasonable prices through revolving funds set up by IRDP. Loans for fingerlings to stock fish ponds were also given to villagers.

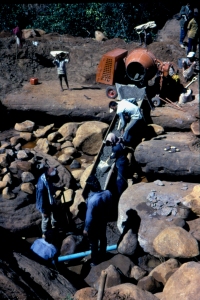

Health and hygiene improved in all of the project villages since the beginning of the program. Like agriculture, the IRDP health initiatives were multifaceted. Clean water systems, usually in the form of wells or gravity fed systems which bring water from higher elevations, formed a corner stone of the health project. Provision of safer water was one of the key elements in the decline of disease in most project villages. Building proper latrines in project villages also contributed to disease prevention.

At least two village level health workers were trained per village and primary health education and sanitation activities are centered around these workers. It was the village health workers task to motivate villagers to drink clean water and maintain general cleanliness. Many of the villages were fenced to prevent animals wandering into residential areas due to awareness raising by village health workers and the practice of medicating mosquito nets has proved effective in reducing the rate of malaria in some villages. Village health workers also maintained revolving drug funds. MCC donated chests of medicine that were distributed to villagers at reasonable cost. The health worker then bought medicines to replace those purchased. The revolving funds were designed to make reasonably priced drugs locally available. Supporting the district health team immunization, birth spacing, and malaria programs was another important part of the health program. In some project villages, immunization coverage of children and women of child bearing age was almost 100%. Awareness of the importance of vaccination also increased. District health officials educated villages about birth spacing, but with varied acceptance.

Mai District 1999

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

mobile library (2000)

Prior to the IRDP, children, especially girls, in many project villages had little opportunity to study. Education has been made a project priority with the IRDP providing tin sheeting and concrete flooring while the villagers provided wood and labor to build schools in more than half of the project villages. In some villages, books were provided for students in the first two grades on the revolving fund model. Students rented books at half of the purchase price when they begin studying and if the book was damaged by the end of the year they had to pay the other half. With the money earned from book rental, new books could be purchased after a few years. Through cooperation with Church World Service, MCC also organized workshops to upgrade teachers skills and initiated creative after-school programs. Trainers demonstrated the use of local materials and new teaching methods to make learning more interesting for the students.

In several project villages, non-formal education programs were initiated. IRDP provided a training for the instructors as well as books for the classes. In some villages, kerosene lanterns to accommodate night classes and stipends for the teachers were given as well. Class subjects ranged from adult literacy to agriculture, animal husbandry and village sanitation, and were very popular among the villagers. Adult literacy in particular benefited village women who often hadn’t had the same educational opportunities as the men.

In several project villages, non-formal education programs were initiated. IRDP provided a training for the instructors as well as books for the classes. In some villages, kerosene lanterns to accommodate night classes and stipends for the teachers were given as well. Class subjects ranged from adult literacy to agriculture, animal husbandry and village sanitation, and were very popular among the villagers. Adult literacy in particular benefited village women who often hadn’t had the same educational opportunities as the men.

In more recent years, IRDP made particular efforts to develop women in the project communities. Villages were encouraged to include women in the development decision making process, and gender awareness trainings were held in some of the communities. Income generating activities sought to support and strengthen women’s management skills. The focus of these activities revolved around development of silk production and weaving skills. Villagers acquired new techniques and higher quality mulberry seedlings to produce improved silk received at the Phonsavanh Sericulture Training Center. One family from Ban Nasa, the first IRDP family to join such a training, was recognized throughout Houa Phan province as a model family for high quality silk production. Workshops were also held in natural dyeing, quality control, color matching and other skills important in making weaving more marketable both inside and outside of the Lao PDR. Development of traditional weaving skills gave women and their families an important source of income.

Training was a central part of the IRDP. All the sectors of the Integrated Rural Development Program: agriculture, health, education and women’s development, depended on well trained and dedicated village volunteers. The project dedicated much time to the training of these committed people. Just as important to the projects, however, were well trained district government counterpart staff and MCC staff. District counterpart and MCC staff benefited from study tours to Thailand, Bangladesh, and Vietnam in order to raise understanding of development processes in the region; and workshops on subjects ranging from upland agriculture, health, education, to project management and gender awareness strengthened their skills and knowledge. While material aid was an important part of MCC’s work in the Lao PDR, trained development workers was a resource that would provide far greater benefit to the Lao people in the long term. MCC believed and still believes that this capacity building will be the longest lasting legacy of its work in the Lao PDR.